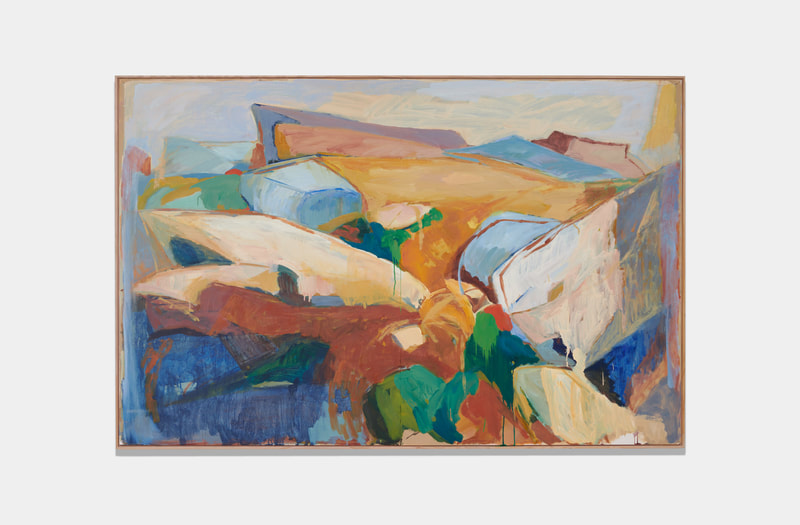

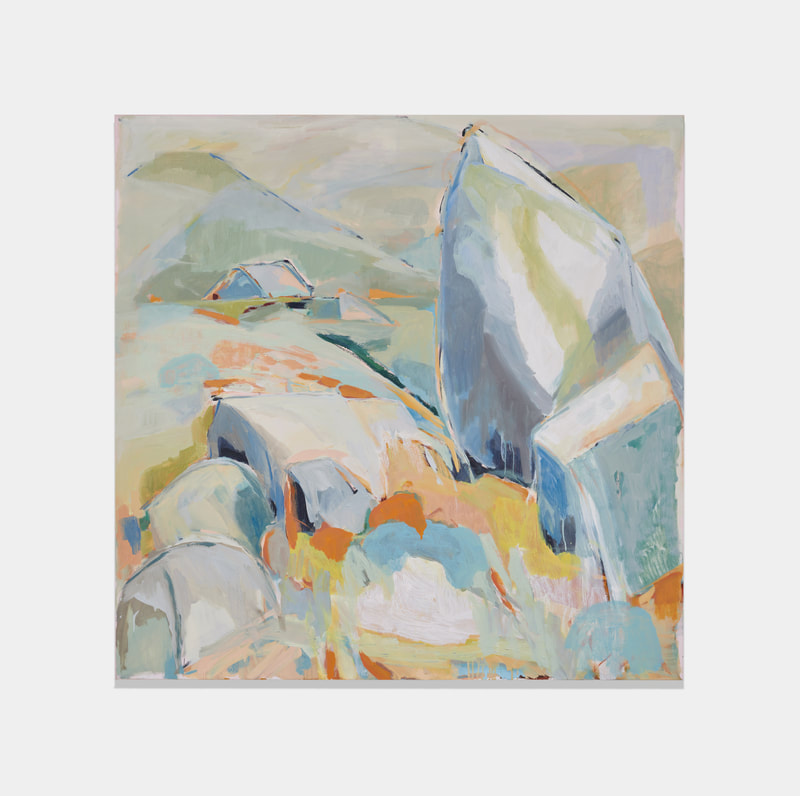

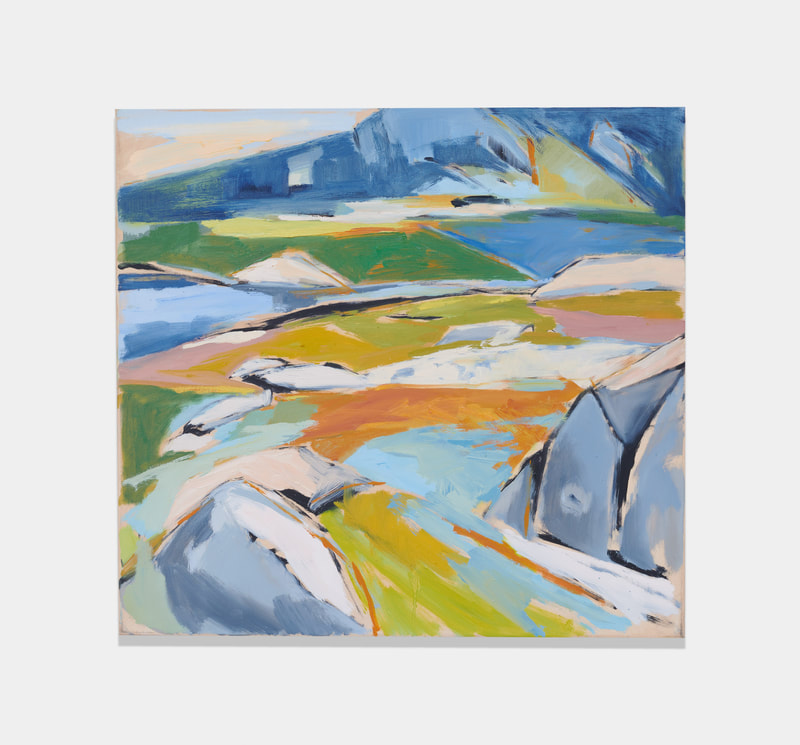

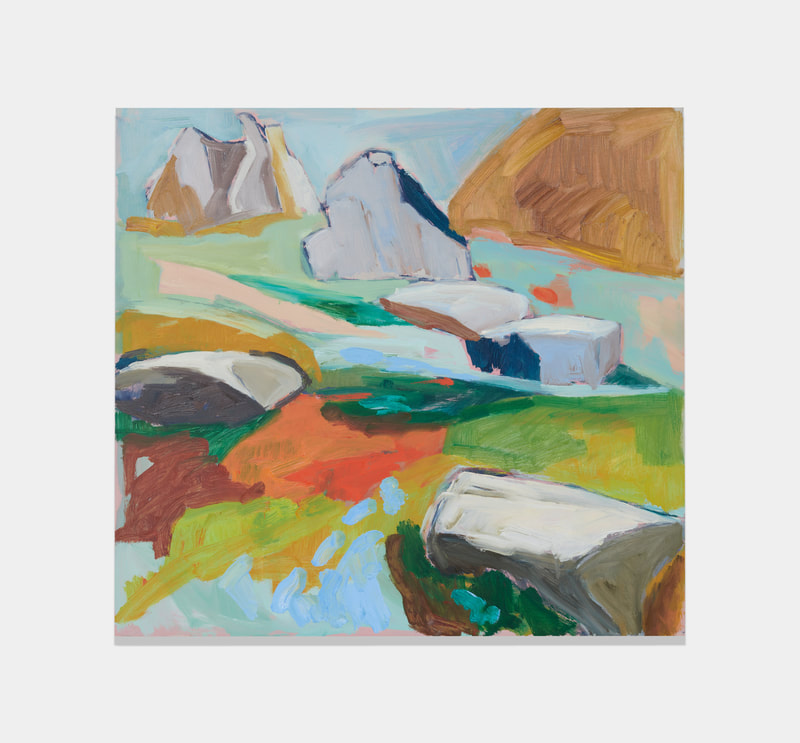

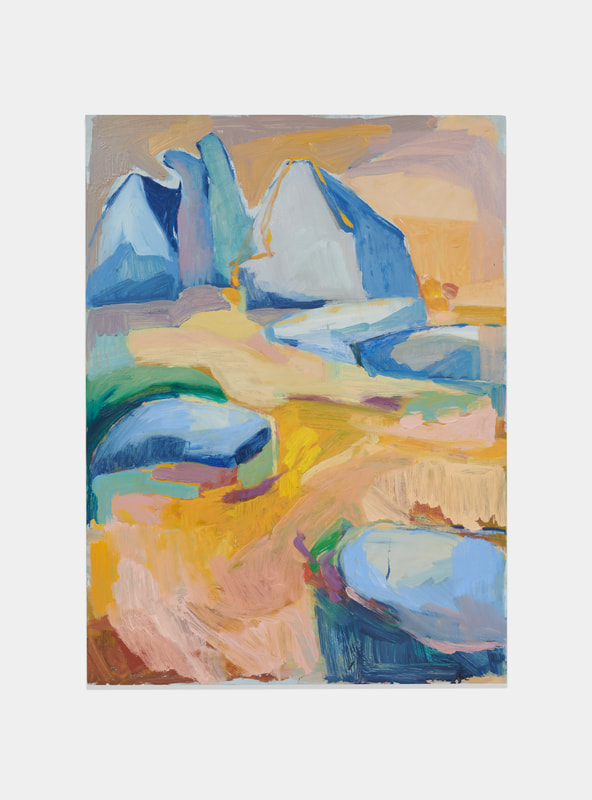

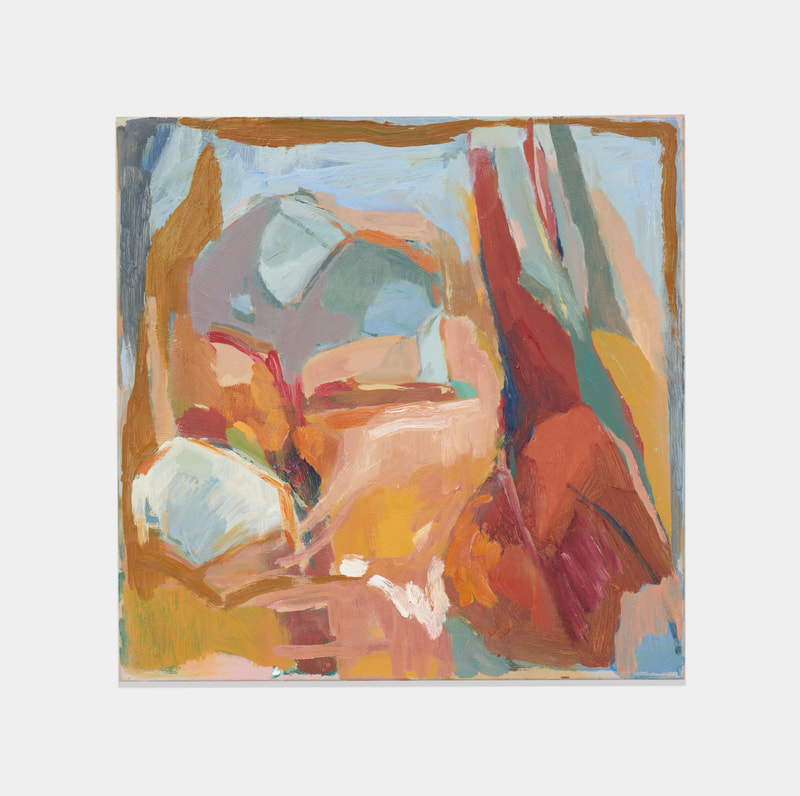

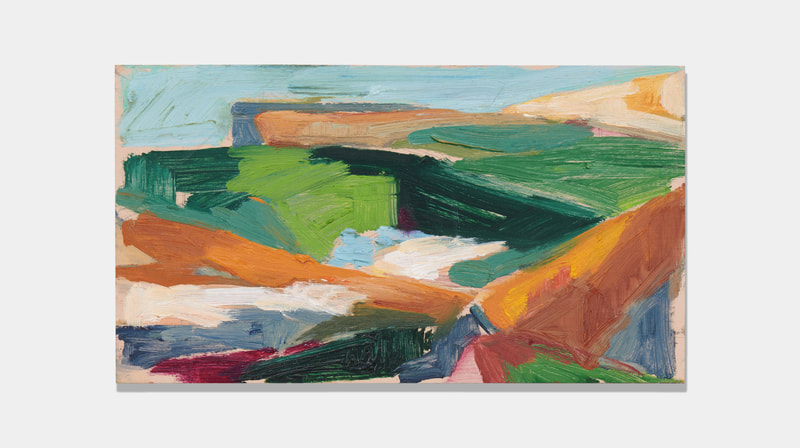

Ochre Lawson’s exhibition ‘Above The Tree Line’ continues her fascination with the wild. It is her deep connection with landscape, ecosystem and nature that is at the forefront of this painting practice. The work in this show is the result of much time spent trekking and camping in the Kosciuszko National Park. Lawson moves through this alpine wilderness with a comfort that comes from her respect for the area and its wildlife. These trips are as much about allowing the land to seep into her and to strengthen her relationship with her surroundings as they are about capturing a likeness. The sketching and observation that occurs is channeled into the surfaces of the works, the peaks and troughs, rivers and rock slip in and out of abstraction with ease. The paintings are loose and free, they express what I feel is a joy and awe for the environments that they depict. The palettes that Lawson selects are often born out of experiencing a flower, foliage or animal and then building the rest of the colour palette around this. In many cases we see how competent Lawson is in the way she is able to highlight, contrast and in some works even indicate camouflage in the environment. The gesture and mark making is expressive and this energy is felt when viewing the paintings. There is a sense of power in the compositions that is often created through the mountain ranges, boulders or in some of the lower lying terrain through the angles and verticality of the tree scapes. The tree line in this show creates a division in the landscape. The freezing cold, wind and snow at some of these altitudes mean that these highland environments are devoid of trees. However elevated these ecosystems are, they are still able to produce so many wonders and such beauty. The clarity and freshness, the flow of ice cold river water, the dots of white green from the clumping flannel flowers. I feel that Lawson is highlighting the wonder of life, the abilities of nature to persevere but also how critical it is for us to respect and preserve these sanctuaries. I imagine her sketches are loose and free that they are barely holding onto the paper, I think Lawson struggles to look down at the paper and away from all this awesome beauty as the frost bites in. I think the paintings are a means for her to find a path back to these environments.

In the Southeastern corner of New South Wales sits a 6,900 square kilometre parkland named after its famous Mount Kosciuszko, the highest mainland Australian mountain. The Koscuiszko National Park was the traditional home of two Aboriginal groups – the Walgalu people and the Ngarigo people and sees several rivers rise in the area, most notably the mighty Murray, Murrumbidgee and Snowy rivers. The environment seems to foster so much adventure and thrill and Lawson continues in this lineage. I have had the pleasure of unpacking paintings out of the back of Lawson’s van, sliding them out from a mattress that is suspended above a well organised system of storage that I feel could sustain her on these trips. It certainly struck me as a perfect situation to start to understand her life and practice. The van almost as critical as the brushes, canvas or birch timber boards on which she paints. On another visit to see the gallery space Lawson was pushing out on a trek and we were ready for 10 days of rain. This was never going to slow her down and this passion and playfulness is for me what makes these paintings so joyous. They reflect how Lawson feels about the region and how she remembers it when she returns to her studio. These wild terrains are not for traditional en plain air work and Lawson in many cases is only able to traverse them with the essentials to spend time there.

The colours in these works are so present and bold. The works are almost as much in the colour theory and relationships as they are the mountains and water. Despite the harshness of the environment Lawson is able to bring a new representation to the scenes through very clever use of colour. The work Snow Gums and Wombat, 2022 is hyper in it’s purples and pinks but then grounded through the greens and this work is a very clever example of how Lawson is able to use colour to allow more representational elements to sit back into their environment. The wombat and kangaroo settle into their surroundings and speak to the camouflage they often take advantage of in the wild. It is only after close study of the work that a figure reveals itself. I can’t help but think this is Lawson trying to render herself in with as soft a touch as possible. The scenes are abstracted through emotional response, a reactive approach to memories and despite starting out as sketches in journals they end as major works on canvas and board. The marks are confident and the renderings feel like celebrations of these lush scenes. Lawson states;

“These paintings try and encapsulate not only the sense of water but the vibrancy of summer grasses and wildflowers found in this environment. I was astonished how soft the grass was in such a rocky environment and the array of greens from soft blue greens to vibrant yellow greens. The soft but vibrant white green of the flannel flowers in massive clumps were everywhere we walked.”

I am filled with positivity after spending time looking at these vibrant works. I can feel the awe that Lawson feels for these environments and the splendour experienced while she is visiting them. I think that Lawson would like the viewer to enjoy her responses and emotions but to also reach out into the wilderness on their own adventures. To appreciate all the beauty and tranquility that the land has to offer. These mountains and rivers are in our psyche and part of our heritage. They need to be experienced, respected and passed onto future generations to enjoy. I don’t doubt that more adventures await, that paintings will most likely continue to slide out from the vans mattress but most importantly that Ochre Lawson will continue to share her unique ability to capture how she feels in these wonderful parts of our land.

James Kerr, 2022

Click to access Catalogue

In the Southeastern corner of New South Wales sits a 6,900 square kilometre parkland named after its famous Mount Kosciuszko, the highest mainland Australian mountain. The Koscuiszko National Park was the traditional home of two Aboriginal groups – the Walgalu people and the Ngarigo people and sees several rivers rise in the area, most notably the mighty Murray, Murrumbidgee and Snowy rivers. The environment seems to foster so much adventure and thrill and Lawson continues in this lineage. I have had the pleasure of unpacking paintings out of the back of Lawson’s van, sliding them out from a mattress that is suspended above a well organised system of storage that I feel could sustain her on these trips. It certainly struck me as a perfect situation to start to understand her life and practice. The van almost as critical as the brushes, canvas or birch timber boards on which she paints. On another visit to see the gallery space Lawson was pushing out on a trek and we were ready for 10 days of rain. This was never going to slow her down and this passion and playfulness is for me what makes these paintings so joyous. They reflect how Lawson feels about the region and how she remembers it when she returns to her studio. These wild terrains are not for traditional en plain air work and Lawson in many cases is only able to traverse them with the essentials to spend time there.

The colours in these works are so present and bold. The works are almost as much in the colour theory and relationships as they are the mountains and water. Despite the harshness of the environment Lawson is able to bring a new representation to the scenes through very clever use of colour. The work Snow Gums and Wombat, 2022 is hyper in it’s purples and pinks but then grounded through the greens and this work is a very clever example of how Lawson is able to use colour to allow more representational elements to sit back into their environment. The wombat and kangaroo settle into their surroundings and speak to the camouflage they often take advantage of in the wild. It is only after close study of the work that a figure reveals itself. I can’t help but think this is Lawson trying to render herself in with as soft a touch as possible. The scenes are abstracted through emotional response, a reactive approach to memories and despite starting out as sketches in journals they end as major works on canvas and board. The marks are confident and the renderings feel like celebrations of these lush scenes. Lawson states;

“These paintings try and encapsulate not only the sense of water but the vibrancy of summer grasses and wildflowers found in this environment. I was astonished how soft the grass was in such a rocky environment and the array of greens from soft blue greens to vibrant yellow greens. The soft but vibrant white green of the flannel flowers in massive clumps were everywhere we walked.”

I am filled with positivity after spending time looking at these vibrant works. I can feel the awe that Lawson feels for these environments and the splendour experienced while she is visiting them. I think that Lawson would like the viewer to enjoy her responses and emotions but to also reach out into the wilderness on their own adventures. To appreciate all the beauty and tranquility that the land has to offer. These mountains and rivers are in our psyche and part of our heritage. They need to be experienced, respected and passed onto future generations to enjoy. I don’t doubt that more adventures await, that paintings will most likely continue to slide out from the vans mattress but most importantly that Ochre Lawson will continue to share her unique ability to capture how she feels in these wonderful parts of our land.

James Kerr, 2022

Click to access Catalogue